The labour market in China is in its infancy. It is, in fact, incorrect to speak of a labour market in China at all; there are many disparate situations where we find working people. Although discussion will be on industrial workers it should not be forgotten that there are still more than 200 million peasants working the land in China, however for brevity these must be excluded from discussion. The state began allocating labour in the 1950s and continued until the 1980s when the attempt to commodify labour began. However, the creation of a labour market has not seen the state wither away; instead it has turned its already considerable repressive powers towards the task of creating a Labour market. Polanyi argued that the creation of markets involved a dramatic increase in the coercive power of the state; this is in marked difference to others who emphasise the natural germination of markets, which occur where the state withdraws from the economy as is typical with most economists.

In an examination of China, Polanyi’s account is by far the more convincing than that of conventional economists. Chinese workers have been reshaped into commodities. This has first been done by the central Chinese state through the smashing of the “iron rice bowl” and the stripping of state provided welfare from the employed, and the exclusion of China’s vast migrant workforce from what little support remains. Moreover, enforced redundancy and bankruptcy have created vast reserves of the unemployed, “freeing” them to find their wage on the market. These reforms were met by a series of Labour Laws, intended to mitigate their negative effects. However, the laws concerning minimum wages, factory conditions etc. go largely ignored due to a second movement towards commodification.

Local government has received much devolved power; for example, in fiscal terms, China has perhaps the most devolved government in the world. In return for this power, local government is charged with fostering economic growth, this usually entails the circumvention of these labour laws. Sole responsibility for the bypassing of these laws should not be levelled at the local state. For example, 78% of state-owned enterprise employees and 95 percent of state-owned enterprise retirees were to be covered by the state-run pension scheme. This reform replaced schemes run by individual enterprises but will not be honoured because of the fiscal limitations of the central state.

There are obvious benefits to China’s current configuration, Chinese workers no longer need to contend with the repression Maoist state, and there have been notable relaxations since the Tiananmen Square Massacre. However, this internal confrontation has been replaced by an external one; workers now have to combat the combined legal departments of several transnational corporations. For years they have been engaged in intensive lobbying against the extension of further labour rights in China, Arrogantly declaring that the labour laws in place, already largely unenforced, are enough for China’s workers.

The creation of a labour market has required de jure, and some de facto, ending of lifetime tenure. In 1983 state-owned enterprises were ordered to hire new employees on a contractual basis, this began the drive to convert labour into a commodity, to be bought and sold as a commodity, and abolished the socialist conunitment to full employment. This was consolidated in the mid-1990s with large scale redundancies at SOEs. However, those who still enjoy urban state sector employment remain very immobile; the real effects of market reforms have been felt by the vast and growing rural-urban migrants. The dissolution of the communes led to the creation of a vast migrant labour force, which numbered around 50 million in the late 1980s, and over 150 million now.

This process shares similarities with the making of the English working class: peasants, handicraft workers, artisans and small manufacturers all suffered displacement as their livelihoods were destroyed, whether, through land enclosure or market competition from more productive capitalist fawns and factories. However, in England as the attempt was made to commodify labour in Britain a countervailing measure arose to protect society: Polanyi interpreted legislation concerning public health, factory conditions, social insurance, public utilities, municipal services and trade union rights in Victorian England as countervailing measures to check the societal effects of the unfettered expansion of capital.

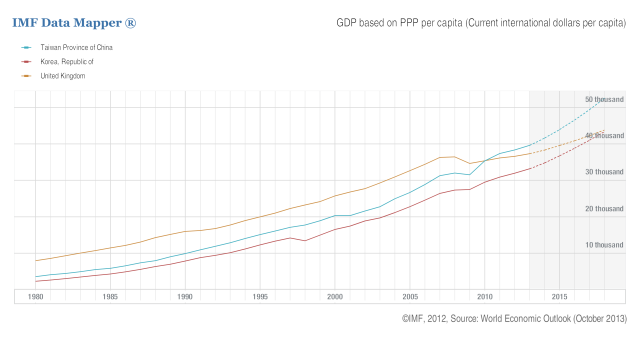

This countervailing measure is far from obvious in China. The expansion of the state required to commodify labour is described above. However, the application of the commodity fictions has only been partially implemented. The local state, at times, undermines the institutions designed to embed Labour within a social minimum. Deng aimed to refashion workers as commodities, to be bought and sold. However, the appeal of the Chinese economy was not just cheap labour; there is a wealth of the desperately poor in the world. China succeeded because its labourers were healthy, educated and disciplined. A population more literate, more educated, and with longer life-spans than any country with a comparable GDP, entered the world market in the 1980s. This was achieved with meal Communes and urban Danwei which operated as miniature welfare states, providing cradle to grave security.

The communes have long since been dissolved and so, as SOEs are transformed, most working people have lost access to their social safety net, including pensions, housing, health care and increasingly even primary and secondary education. To illustrate, after three decades of reform, healthcare is in freefall and the World Health Organisation ranks China last in terms of equal access to healthcare. Furthermore, China alone is helping to partially refute the idea that “wealthier is healthier.” The marketisation of its healthcare infrastructure has caused improvements in health to accrue more slowly, and less equitably, than in any comparable state in history — the poorest now go without healthcare altogether. As discussed in my last post, the countermovement against the commodification of land is notable for its weakness and for the damage which has been wrought in its absence; regrettably the same is true, to a lesser degree, of labour. Labour laws exist in China; there are a number of rights which have been introduced, from pension reform to minimum wages. However, the Double Movement is not a matter of formal labour rights. If rights such as those above go unenforced, as they do in China, they cannot be described as constituting a Double Movement.

After examining the conditions of workers in China; both their hardship and their lack of protection offers evidence that might be used to refute the existence of Polanyi’s Double Movement. However, informal institutions of embedding have arisen in order to overcome the abusive application of China’s labour laws. This essay will argue that, as with business in China, rural-urban migrants have developed a complex system of guanxi to insulate themselves from the market. The work of Granovetter describes the limits of spot markets between anonymous individuals to transfer information and build social trust. Moreover, it helps us to understand that legal protection and social security are not the only ways in which the economy can be embedded. Within China, informal systems of embeddedness have come to be incredibly important.

A brief description of the origins of China’s migrant labourers is necessary to place them in the correct context. Revolutionary China used a hukou, or household registration system, to all welfare provision to its population. It also constituted an intrusive method of social control, preventing all but a limited amount of internal migration. Initially registering the population was simply about finding out the numbers involved, but hukou soon became a tool to restrict mobility. The hukou system’s weakening has granted labour the freedom of movement around China, but it also prevents migrant workers from claiming the pensions, schooling, unemployment benefits, etc. enjoyed by those who have an urban hukou. In official Chinese parlance peasant workers in urban jobs are not migrants; as it would denotes a more settled status. They are a “floating population,” without the rights that those who possess urban hukou enjoy. It is this group who make the most extensive use of guanxi as it is they who lack the most basic of protections.

Guanxi is an informal set of ties and obligations whose origin can be traced back to Communist China. In contemporary business relations its importance is well documented (and I will discuss it more tomorrow). Granovetter’s study examined the behaviour of individuals within a developed market, and found that they often substituted embedded social relations for rational economic maximising behaviour. A similar and more intense version is employed to glean useful information from fellow migrants to find work, and protect themselves from unemployment. To illustrate, it is argued that because of the guanxi between current migrant workers and potential migrants as few as just five to ten percent of newcomers to Chinese cities could not find work within a week of arriving. The emphasis placed on guanxi can help us to understand why it is that China’s rural migrants can survive and remain productive in such a hostile environment.

The demands made by the market can prove utterly disastrous for human beings if their basic needs are not protected. However, the Double Movement is more fundamental than this. Guanxi has helped to explain the survival of Chinese workers in a hostile environment, often devoid of the social protection Polanyi argued was essential; however, this only addresses one aspect of the Double Movement. It is also fundamental in embedding economic relations in a legal system that ensures that the commodity fictions are upheld in a market-society. As explained the Double Movement is not anathema to markets, it is a necessary condition.

Fred Block discusses the embedding of the economy in “law, politics and morality,” the economy insist be embedded within reasonable and lawful practices. Thus, even an approximation of a market system requires embedding within a social minimum. The evasion of Labour standards illustrates the weakness of the Double Movement in China. This view, though controversial in Polanyi’s time, is now firmly embedded in the new institutional economics of people like Douglass North, Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson.

Non-payment of wages is a major problem in China, sometimes used to discipline workers, it is used to ensure workers do not quit, as if they do they risk losing all right to unpaid wages. It is incredibly widespread, in a survey it was reported to have had affected 72.5 percent of workers. It is cited as a major cause of protest in China; but by using it to discipline workers further protests are being prevented. The non-payment of wages is a method used in China by capitalists to enforce discipline and expropriate capital from their workers. This practice is credited with allowing such a large amount of wealth to be accumulated by such a small group, in such a short amount of time.

At times this is discussed as a shocking denial of human rights, the simple right to be paid what one has agreed as remuneration for one’s labour. It is presented as an example of how brutal capitalist development has been in China. But, the true interpretation of this practice is rather different. Capitalist exploitation under a market system involves the sale of labour as a commodity. The theft of labour is evidently not part of this. This practice illustrates again the weakness of the Double Movement in China; it has failed to provide an adequate legal framework to ensure wages are paid on time, or even at all. Without a Double Movement to embed market structures they don’t exist. You don’t get capitalism you get something even more brutal.

In law the situation concerning labour appears far better than that concerning land. However, in practice both appear to be subject to the damaging infliction of commodity fictions. Giovanni Arrighi suggests that the Chinese state has presided over gradual economic reform and met these with countervailing actions to promote a “synergy between an expanding national market and a new social division of labour.” However, this represents an astonishing, though predictable, misreading of what is occurring in China. With regard to labour the Chinese economy tacks not only the protection necessary to ensure wages are paid on time, but reform has also hollowed out the institutions that made the Chinese economy a success in the first place.

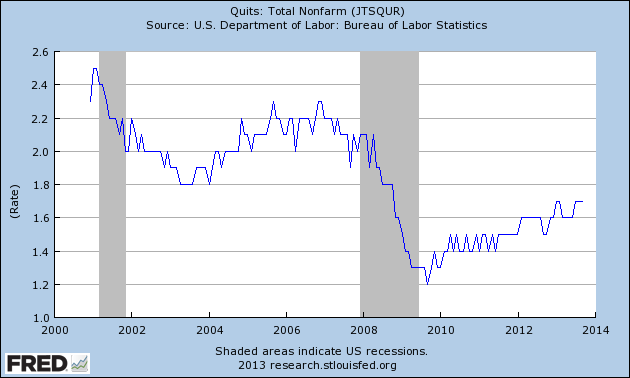

Since I wrote started researching China about half a decade ago a lot has changed. It’s a country that moves at an astonishing rate. Over the past decade, China has rapidly expanded the numbers going to university from from 2.2 million in 2000 to 6.6 million in 2010 students. Job creation hasn’t keep pace and there were 100 job applicants in mid-2013 for every 80 jobs which require a university education in China. The scenario was reversed for jobs which don’t require tertiary education, there were 100 applicants for every 125 slots in China. This has led to a narrowing in wages. Since 2009, professional wages have climbed 12 percent annually. In the same period, average wages in manufacturing, agriculture, and construction have risen 14 percent annually. I’ll chalk this one up as a success for Polanyi’s Double Movement and a sign I was probably too pessimistic 5 years ago.

China has been successful in destroying the old institutions, which allowed it to enter the world economy and out perform all previous expectations. However, they have not been replaced with new institutions to guarantee further success, although some elements are improving. On one level this is evident in the endemic non-payment of of wages, and the callous exploitation of the local state. You can also see the frictions in the mass gathering incidents documented by Jamie.

I would argue there are two seams to the protests now occurring in China. These can be used to locate where people feel threatened by China’s Great Transformation. Some occur because some workers have been left to the mercy of the market, protesting against enforced SOE dissolution, low wages, and a scandalous marketisation of basic services; such as healthcare and education. Others occur precisely because the same set of commodity fictions are not enforced, people are robbed of their labour and land because a market has not been instituted inside reasonable institutions. The same is true in the countryside where Chinese robber-barons have seized huge tracts of land. Both stem from the same source, the weak countermovement in China. If action is not taken to embed the market, then the ecological and human damage that will result will be matched by the collapse of China’s economy. We’ve heard lots about China’s capitalists in passing, but I’ll go into more detail tomorrow.

You must be logged in to post a comment.